Connecting with Wine Growers the PICA Way

- Nov 10, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 13, 2021

Before lockdown I visited the Cavit co-operative group in Trentino to see how it applies cutting edge technology to improve its wines and the environment. Last week I caught up with the head of agronomy on zoom to find out about its impact in a year like this.

Colour-coded vineyard parcels, including Schiava Gentile, on the PICA app on a Cavit agronomist's smartphone

In the tiny village in deeply rural France where I’m often based, we always know when a storm is about to whip up. Suddenly the local farmer is hurrying down the road with her putative sheep dog to round up her sheep from whichever hillside they’re on and drive them back up the road at speed to the farm, desperately trying to stop the still-hungry flock from being sidetracked by temping looking greenery (in truth, the not very well trained dog is just as likely to be sidetracked as the sheep, but we’ll gloss over that). On a normal day, the flock, fully fed, lumbers slowly back home at the end of the day, neither they nor the farmer in any hurry.

The weather can come from any direction and change without warning in this high, remote part of France. We’ve had hail the size of small golf balls that dented the whole of our car and broke a window. We’ve had a mini tornado and lightning that uprooted large, old trees and snapped others in half. The farmer rounding up her sheep at an uncharacteristic time of day is our warning to batten down the hatches. Her warning comes with a call on her mobile from the mairie. The maire will have been alerted by the nearest weather station.

Although the most basic of systems, it works because there are only two farms (both sheep) and there are mobile phones, but what do you do on a larger scale? Sheep farming isn’t my realm (though you could be forgiven for beginning to wonder), but I can tell you what one consorzio of 11 wine co-operatives in northern Italy does.

Trentino's tiny vineyard plots facing in all directions to capture the best exposure on the steep slopes

In a nutshell, Cavit harnessed a massive amount of viticultural, geological and meteorological data, gathered over many years, and combined it to create an integrated mapping platform, a software programme known as PICA (Piattaforma Integrata Cartografica Agriviticola). For each vineyard, PICA holds details of soils, grape variety, age of vines, cultivation methods, elevation, exposure, gradient, daylight hours and a complete catalogue of climatic data. As a digital interface it provides computers, tablets and smartphones with detailed images of vineyards, an opportunity to explore and resolve problems and receive input on cultivation updated in real time. The objective is twofold: to improve wine quality and to improve environmental protection and sustainability.

The co-operatives’ growers receive sms messages, emails and/or voicemails, according to the content of the message and which form of communication they use. A grower using a smartphone might get a longer or more complex message via voicemail rather than sms. Every single grower can be advised in real time on the best way to plan work, how to monitor and target treatments against insects and fungal disease to keep treatments to a minimum, and how and when to check weather and climate conditions and the ripening of grapes in the run up to the harvest.

It’s tailor-made and two-way: growers can contact Cavit’s Technical Assistance service if they have a query and they can input data and photographs on the app. In the past, information about spraying against pending disease would be posted on winery doors and everyone would spray, in many cases unnecessarily. Now the focus is on individual vineyards and treatments are on a much smaller scale and much more precise.

Steep, vine clad slopes, cheek by jowl with mountains in the clouds and sunshine breaking through – so very Trentino

Cavit has more than 5250 growers. By early November last year, the PICA team, led by director and chief agronomist Andrea Faustini, had sent out more than 200,000 sms messages to growers. This year, they have sent out 30% more already, the increase as a result of Covid-19, not to it being a particularly challenging year, although abundant summer rain did create conditions favouring downy mildew and botrytis – both successfully managed, thanks to PICA.

During the season, Cavit’s agronomists scout and scour the patchwork of tiny, steep plots (80% pergola-trained and all picked by hand) and then feed back information. Standing in the vineyards, me looking at a minutely detailed, colour-coded vineyard on agronomist Andrea Colombini's smartphone, he explains: “The app is massively complex. You are examining a single plot, but it might apply to a bigger area.” At harvest time, an agronomist might be “saying when one plot should be picked or just a few rows”. In the 200 metres between the top and bottom vineyards on this particular slope, there’s a week’s difference in picking times. By the end of each season (the bulk of the harvest was over by the close of September this year – just the Cabernet remained for the first week of October), the 19-strong agronomist team has made close to 5000 checks on ripening alone.

In a region where families have been tending, usually multiple, small plots of vines for generations, you might assume that they wouldn’t need to be advised when and what to do in their own vineyards. And some of them certainly felt that way when PICA was introduced in 2014, but now almost 100% of Cavit growers are signed up to it. That’s more than 5250 growers, 6,350 ha of vineyards, and over 60% of Trentino’s wine production. No wonder Cavit is proud of having “the most technically advanced technological platform in Italy for the implementation of smart, environmentally sustainable viticulture.”

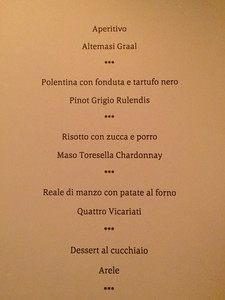

Always aim to hit the truffle season in Italy – a winning pairing here of polenta, fonduta and black truffle with Rulendis Pinot Grigio 2017 at Casa del Vino della Vallagarina, Trentino

Not that Cavit alone created PICA. Research and development began officially in 2010 in collaboration with two leading Trentino research centres, the Edmund Mach Foundation (FEM) and the Bruno Kessler Foundation (FBK). On Cavit’s side, the programme has been steered from the outset by Andrea Faustino, earning him his nickname, the Papa of PICA. In addition to data collected by the wineries since the 1980s, PICA now has all the data collected over the last ten-plus years of the programme.

Apart from making decisions quickly and specifically, improving quality of both wines and the environment and enabling Cavit to reach out to growers more effectively during this year’s pandemic, PICA has enabled Cavit to respond to climate change in terms of which varieties are grown where. Müller-Thurgau plantings have moved from an average altitude of 500m to 600m. Pinot Nero and Chardonnay for Trentodoc metodo classico are now on north-west and north-east exposures; 30 years ago these were not recommended, southern exposures were. On southern exposures now, they can grow Gewürztraminer, Sauvignon Blanc on the right kind of soils (clay with basalt, or glacial soils), and some Chardonnay and Pinot Nero for still wines.

Cavit's top Altemasi Trentodoc: Riserva Graal in the 2012 vintage

As far as specific wines are concerned, the Altemasi Trentodoc (classic method sparkling) wines have become increasingly important and successful. Having tasted the range of Brut NV, Millesimato 2015, Rosé NV, Pas Dosé 2012 and 2013, and Graal Riserva 2012 (72 months on lees), it’s obvious why. These are stylish, precise wines with, in the case of the vintage wines, depth and length too.

In fact, those adjectives could also be applied to various still wines that have been born out of the benefits of PICA, among them Rulendis Pinot Grigio, a Trentino Superiore of aromatic intensity and fine structure from two low-yielding vineyards planted around 30 years ago at over 500m asl, much higher than usual for Pinot Grigio; Maso Toresella Chardonnay Trentino Riserva, a sophisticated barrel-fermented Chardonnay from a 6.5m vineyard at 245m near Lake Toblino; Bottega Vinai Schiava Gentile Rosato, a soft-textured but crunchy red-fruited rosé made from the local Schiava grape grown on basalt terraces either side of River Adige; Bottegai Vinai Pinot Nero, aged for just over a year in 80% oak, the majority barrel, about one third new, producing a wine with an attractively savoury finish; Brusafer Pinot Nero, a Trentino Superiore from hillsides around Trento itself, aged for nearly three years in oak barrels and tonneau, one third new; and Quattro Vicariati, a 70% Cabernet Sauvignon Bordeaux-blend Trentino Superiore aged in oak barrels for 18 months.

The Bottega Vinai range is sourced from the top 3% of vineyards in the Cavit stable. The Rulendis, Maso Toresella, Brusafer and Quattro Vicariati come from the most expressive, extreme, high altitude, individual parcels to which Cavit has access.

Boutinot Wines is Cavit’s UK importer. It doesn’t sell the complete range of Altemasi sparkling wines or the Schiava rosé, but sells the others above and many others.

Photographs by Joanna Simon

Personal numbers help link services, records, and daily tasks. They can support access, billing, and identity checks across apps and offices. Still, many people prefer privacy-first paths that reduce sharing. Some systems now let users verify without personal number while keeping trust and speed. Clear rules, consent prompts, and secure storage lower risk. Simple alternatives like tokens, codes, or temporary IDs can work well. As digital life grows, smart design balances ease, safety, and choice for everyone. Education and audits strengthen confidence over time for users and providers alike globally.

Click Here

Bold and eye-catching, Beth Dutton Clothing reflects her fearless personality. From coats to dresses, the styles are unique and instantly recognizable. If you want to take it up a notch, layering with a Western Jacket makes the outfit even more powerful.

I recently learned about the PICA approach to connecting with wine growers, and it sounds fascinating. The way they foster relationships and emphasize sustainability is truly commendable. It got me thinking about how different industries, like tech and agriculture, can learn from each other. For instance, in my field, we use Kubernetes for developers to streamline and manage complex applications. Similarly, PICA's method of integrating community and innovation could be a game-changer for wine growers. It's all about creating efficient, supportive systems, whether in tech or agriculture, to achieve the best outcomes.